A Jobs Agenda for the Right

Over the past four years, the unemployment rate has dropped from a high of 10% in October 2009 to 7% this past November. The fact remains, however, that an unemployment rate of 7% is much too high, and that even this troubling rate masks the true weakness of the labor market.

A quick review of the most recent labor-market data tells the story. A broader measure of unemployment includes both workers who want full-time jobs but have to settle for part-time work and workers who are marginally attached to the labor force. Defined this way, the unemployment rate in November was 13.2%, more than four percentage points higher than it was at the beginning of the Great Recession. The economy is home to 1.3 million fewer jobs today than when the Great Recession began. The three-month moving average of employment gains is currently 193,000 jobs per month. At that rate, the Brookings Institution's Hamilton Project calculates that the jobs gap will not close until more than five years from now.

Low-skill workers in particular are still suffering terribly in the labor market. The unemployment rate for African-American teenagers is 35.8%; for white teenagers, it is 18.6%. Just under 11% of high-school dropouts are unemployed. Disability rolls have grown as the unemployment rate has risen.

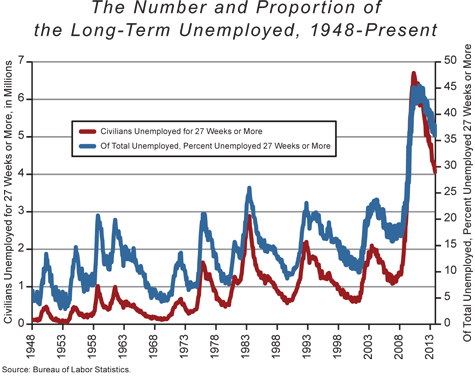

Long-term unemployment is an even more daunting problem. Both the number of long-term unemployed workers (who have been actively looking for work but unable to find jobs for 27 weeks or longer) and their share of total unemployment are at post-war highs. The chart below describes an economic and human catastrophe — productive economic resources asking to be used are sitting on the sidelines, as millions of unemployed workers lose their sense of dignity, their dreams and aspirations, and their ability to live a flourishing life.

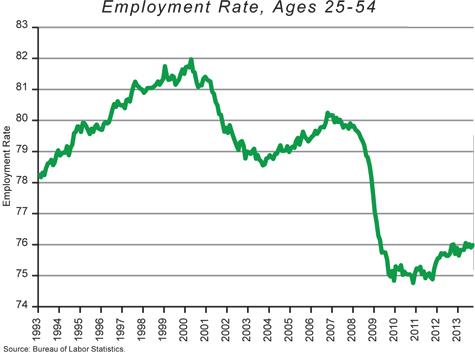

The labor-force participation rate fell to its lowest level in over three and a half decades in October. The share of the population with jobs — a broad measure of the overall health of the labor market — plummeted during the Great Recession and has not increased during the recovery.

Some dismiss this employment decline as a consequence of the fact that the population is getting older and that young people are working less. But this argument is easily refuted by looking at the employment rate for Americans between the ages of 25 and 54. As the chart below demonstrates, the employment rate for people in their prime working years — when essentially everyone is too old to be in school but too young to retire — has a long way to go before it recovers from the Great Recession.

Unfortunately, the longer such workers are without a job, the more these economic and social problems compound. Indeed, if the situation does not significantly and quickly improve, we will be living with the effects of today's labor market for decades to come. Many of today's young workers who are unable start their careers will have damaged work lives for years into the future. Many of today's long-term unemployed will likely never finish their careers — at least not in the manner they had planned. Some of the damage will be borne by the children of the long-term unemployed. Tomorrow's public-assistance rolls will be shaped by today's labor market. The economy's productive capacity years into the future depends to a large degree on the health of the labor market today.

This employment crisis is one of the most important and immediate social and economic problems facing the country today, and none of our elected leaders can afford to ignore it. Yet both parties are more or less doing just that. The Democrats talk about jobs policies, but their approach to the problem — with its emphasis on massive short-term fiscal stimulus and inefficient public spending — has proven neither popular nor (at least in the form attempted at the beginning of the Obama years) up to the challenge. It consists of the timeworn economic mantras of the left and is not equipped to address the problems we now have.

Republicans are, if anything, worse off. They often refuse to even acknowledge the problem, or to acknowledge the fact that it requires ambitious policy solutions. They, too, mostly repeat familiar formulas from their party's glory days which offer proposals that do not seem well connected to today's economic realities. Some of their ideas — fostering a more stable business climate and financing lower tax rates by shrinking a few tax loopholes, for example — could help, but they are not nearly adequate for the challenge America confronts. To offer the public a plausible agenda for a true recovery of the labor market, Republicans will have to dig deeper.

It is, however, from the right and not the left that solutions are likely to come. In the years since the Great Recession, liberal ideas have been tried and found wanting. Conservative ideas and intuitions have not yet been put to work on the problem. If they were, they could well point to some promising answers.

STIMULUS, PROPERLY UNDERSTOOD

However much the left may desire it, another massive short-term fiscal stimulus is politically impossible now, and conservatives are rightly pleased about that. In theory, government spending can support economic growth during a recession, but the practical implementation of short-term fiscal stimulus poses some high hurdles to overcome. It is very difficult to get the timing and composition of such stimulus right, as liberals have frequently found.

This is not to say that conservatives should be dogmatically opposed to any plan to increase employment through government spending. The United States is in its third consecutive "jobless recovery" — despite a recovery in aggregate output, the labor market has seen persistently high unemployment. Jobless recoveries suggest a particular fiscal-policy response: Instead of short-term stimulus as a countermeasure to recession, policy should focus on longer-lived investment projects. The projects selected should have high social value — they should involve things we would want to do even in the absence of a demand shortfall. And some public investments of that sort do present themselves.

Anyone who has driven on a highway in Missouri or has taken an escalator in a Washington, D.C., Metro station knows that the United States could use some infrastructure investment. And expanding public-transportation options from poor neighborhoods to commercial centers could increase economic mobility and the incomes of the poor — a goal conservatives should certainly support. Today's low interest rates only increase the desirability of a multi-year program of high-social-value infrastructure spending.

The 2009 stimulus bill failed to direct funds effectively to such projects, but that does not mean that infrastructure spending, if properly conceived and directed, cannot do a great deal of good. And, of course, to ensure that federal debt is on a stable trajectory, any large increase in spending should be coupled with restraints on the future path of middle-class entitlement spending and a reining in of tax expenditures.

Carefully targeted infrastructure spending should also be coupled with a more pro-growth monetary policy. Monetary policy surely offers the best way to boost aggregate demand in the short term. By keeping the federal funds rate at zero and pursuing its long-term asset purchase program (known as quantitative easing or QE), the Federal Reserve has done much to support the economy during the Great Recession. But growth is still slow and the labor market is still very weak. Is there more the Fed could do?

The Fed has to be careful to avoid responding too aggressively to the weak labor market. Going too far out on a limb could risk its political independence. And, to protect the long-term health of the economy, the Fed's commitment to keeping inflation in check must remain completely credible.

At this point, however, with inflation below the Fed's target and unemployment above it, the central bank is failing to uphold both components of its dual mandate. And the budget and debt-ceiling shenanigans in Washington, contractionary fiscal policy, continued weakness in aggregate demand, and the weak economies of Europe and Asia strongly suggest that the Fed should be more concerned about prices falling too low than rising too high. Given the current economic environment, there are steps the Fed could take to respond more aggressively to the weak labor market without compromising its position and its image as a fierce opponent of (above-target) inflation.

For example, the Fed should stop treating the inflation target as a ceiling for inflation and start treating it as an average to aim for over time. In other words, the central bank's 2% inflation target should be understood as the middle of a band of acceptable inflation rates of, say, one percentage point on either side, and not as the maximum acceptable rate of inflation. This would signal that the Fed will let the economy run hotter by keeping the federal funds rate at zero for longer than many currently expect. The Fed should also lower its unemployment-rate threshold (the point at which it would move to raise the federal funds rate) from its current 6.5% to 6%. The Fed may also want to consider increasing the inflation target for a time to 2.5%, while making clear that the new target is a temporary measure designed to combat the lingering effects of a once-in-a-generation economic crisis.

In addition, the Fed should consider using other measures beyond the unemployment rate in structuring its forward guidance. Many economists believe that the unemployment rate no longer serves as a sufficient measure of the health of the labor market since it fails to capture workers who leave the labor force believing they have little hope of finding a job. The Fed could condition the future path of monetary policy on a combination of labor-market indicators: The unemployment rate should still be included, but the labor-force participation rate, or the employment-population ratio, could be used as well.

Many conservatives have criticized the QE program, but unfairly so. There is good reason to believe that QE has increased stock prices and stimulated demand in the housing market, creating jobs for construction-related workers. And some economists think that QE has had a positive effect on the economy as a signal in and of itself of the Fed's commitment to a strong labor market. Concerns about QE causing rampant inflation in the future are exaggerated. The QE program should continue with no prospect of "tapering" until the labor-market outlook improves, provided of course that prices remain relatively stable. Even critics who argue that QE is no longer effective must acknowledge that the mere threat of tapering increased long-term rates at a time when we need to keep them low. To be sure, unwinding from this program will require great care and will likely be tricky, but the benefits of persisting outweigh the risks at this point.

In short, conservatives should see that there is a role for macroeconomic stimulus in getting the labor market back on its feet. Some limited, targeted, and independently beneficial federal spending can help increase long-term growth and mobility. And monetary policy with its eye on enabling growth can make a big difference.

While such efforts can help establish a foundation of circumstances conducive to growth, they by no means constitute the limits of the government's power to help get Americans back to work. Beyond helping to create a macroeconomic environment that encourages job growth, a conservative jobs agenda should seek to advance policies designed to support employment, remove structural obstacles to job growth, and increase the dynamism and energy of the labor market. In some cases, government needs to get out of the way. But in others, conservatives should embrace energetic but prudent government action.

SUPPORTING EMPLOYMENT

A conservative jobs agenda could begin by pursuing a series of relatively familiar goals that need to be re-emphasized.

To start, rolling back oppressive licensing requirements would be a big help. The Institute for Justice reports that the average cosmetologist spends 372 days in training to receive an occupational license from the government, while the average emergency medical technician trains for 33 days. Which occupation seems like it needs more training? In October 2013 the Washington Post told the story of Isis Brantley, who is required by law to complete a staggering 2,250 hours of training in order to teach hair-braiding to willing customers in Dallas. The government certainly has a role in ensuring that certain occupations are practiced only by well-trained professionals, but it seems obvious that we have gone too far. As part of their effort to put Americans back to work, conservatives should support scaling back unnecessary occupational licensing at every level of government in order to advance economic liberty and create jobs.

A reform of today's disability-benefit system is also essential. The share of working-age adults receiving Social Security Disability Insurance benefits doubled from 2.3% in 1989 to 4.6% in 2009. Program expenditures have increased dramatically as well. SSDI applications track movements in the unemployment rate across time, providing strong support to the hypothesis that many people who would like to work but can't find a job end up on disability. The United States must ensure a basic standard of living for the truly disabled, but no one seriously disputes the argument that SSDI needs to be reformed so that it ceases to offer a permanent alternative to working for people who could be in the labor force. Conservatives should champion this cause unabashedly.

The way we currently treat highly skilled immigrants needs to be rethought too: We bring motivated, ambitious foreigners into the United States to earn graduate degrees, and then we send them out of the country after they've graduated, often against their wishes, just when they are at the point when they could contribute to the economy and create jobs. Any immigrant who earns a graduate degree in America in the physical sciences, engineering, high technology, or mathematics should be granted permanent residency. Highly skilled immigrants are job creators; one in four engineering and tech businesses founded between 1995 and 2005 had at least one immigrant founder. Reforming our immigration laws to admit more highly skilled immigrants is a great jobs program, and should be marketed and thought of as such.

Conservatives should also consider some creative reforms of the unemployment-insurance system. Giving unemployed workers a modest cash bonus when they secure employment has been shown to be effective in shortening the length of unemployment spells, and, if targeted at workers who have a high probability of exhausting benefits, it can actually save the taxpayers money in the long run. It seems implausible that a re-employment bonus would have a large effect on long-term unemployment, but evidence suggests that it would help in addressing shorter unemployment spells. There is also some evidence that giving out lump-sum unemployment benefits may be preferable to the current system of weekly checks. Under traditional unemployment insurance, a worker forgoes his unemployment benefit by taking a job. Lump-sum unemployment insurance may be beneficial because it would mitigate the weekly-check system's incentive to delay starting a job. With lump-sum unemployment benefits paid, say, every month rather than every week, a worker who got a job at the beginning of a pay period could take in both unemployment compensation and a paycheck for that month. If this gets workers off unemployment faster, then the program could save money over traditional unemployment insurance.

And a conservative jobs program should promote entrepreneurship and lower employment costs. We should consider temporarily reducing or eliminating the capital-gains tax on new business investment to help them attract capital, and we should get the government off the backs of entrepreneurs and existing businesses by lessening the burdens of regulatory compliance and licensing requirements.

Conservatives should also push for more states to adopt right-to-work laws. Because unions increase the cost of employing a worker by driving up wages and benefits, weaker unions may lead to faster employment growth. We should consider taking advantage of today's low interest rates to offer assistance to some long-term unemployed workers who want to start businesses. And conservatives should push for increasing domestic energy production — and the jobs that come with it — by allowing for more exploration on federal lands.

These steps offer some straightforward ways to help spur more employment. But to address the kinds of profound obstacles to job growth that seem to confront our country, conservatives will also have to think beyond these familiar categories. Three ideas in particular — relocation assistance, sub-minimum wages with wage subsidies, and worksharing — need to become part of the right's jobs agenda.

FINDING WORK

The Great Recession hit the entire country, but its effects have not been evenly distributed across regions and states. The same is true of the recovery. In fact, the severity of unemployment, the availability of job openings, and the rate of new hires vary quite a bit across the United States today.

In 2012, the unemployment rate was 11.1% in Nevada, 10.5% in California, and 10.4% in Rhode Island. Three southern states — Georgia, North Carolina, and South Carolina — had unemployment rates at 9% or higher. Washington, D.C., Florida, Illinois, New York, and Oregon had unemployment rates between 8% and 9%. In contrast, the unemployment rate was 3.1% in North Dakota, 3.9% in Nebraska, and 4.4% in South Dakota. Ten additional states — Hawaii, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, and Wyoming — all had unemployment rates below 6%. Preliminary data from the summer of 2013 show that similar patterns continue to hold. The labor markets in North Dakota and Nebraska are so different from those in Nevada and California that they may as well be in different countries.

There is noticeable variation in job-openings rates across regions as well. This summer, the rate of job openings in the South was around 20% higher than in the Northeast. There have been some months since the beginning of the official recovery when the West has had the highest job-openings rate, though currently the South has the highest. The Midwest had the lowest job-openings rate early in the recovery but was in second place by this past June.

Hires rates differ as well. The hires rate this summer in the South, for instance, was around one-third higher than in the Northeast. In addition, the trend for hires in the South has been upward since the official beginning of the recovery, whereas it has been flat for the Northeast.

Many of the long-term unemployed living in, say, New Jersey would likely have a much easier time finding a job in North Dakota. Given that unemployment rates, job-openings rates, and hires rates vary so much across the country, it makes sense to help the long-term unemployed move from a bad labor-market region to a better labor-market region.

This help should take two forms. First, we should provide information to unemployed workers about local labor-market conditions around the country. Many unemployed workers simply may not know how hard it is to find a job near their home in the same industry in which they were previously employed, that a different industry is booming, or that a different city or state has far more job openings in their desired field than their current location offers.

A simple two- or three-page document with information about unemployment rates, job openings, and payroll gains by industry could be very helpful and would not cost much. The government already routinely collects and publishes data on local labor-market conditions, so the only extra work involved in implementing this proposal would be packaging and distribution.

Second, we should provide relocation subsidies to the long-term unemployed to finance a good chunk of the costs of moving to a different part of the country with a better labor market. These subsidies should cover a solid majority of reasonable and necessary moving expenses. We may also want to make up the difference with a low-interest loan, with a repayment scheme capped at a small percentage of annual earnings subsequent to their starting a job. Moving is a major investment that requires a fair amount of up-front cash. Many of the long-term unemployed just don't have the money and don't have much access to credit.

These kinds of subsidies should be available only to long-term unemployed workers who live in an area with a poor local labor market. Workers who have left the labor force since the start of the Great Recession should be allowed to enroll provided that they were long-term unemployed before leaving. Subsidies should also be available to workers who were long-term unemployed but have exited within the past few years from long-term unemployment into a part-time job, or into a job that pays significantly less than they earned in their previous job. And workers must move to a destination a good distance from their current residence — say, at least a two-hour drive — to be eligible for a subsidy.

Evidence suggests that encouraging relocation this way would be helpful. A study by the Hamilton Project looked at workers who were unemployed from 2005 through 2008. The study found "substantial differences in reemployment rates between movers and nonmovers [following job loss], on the order of around twelve percentage points even after statistically controlling for years since job displacement, age, educational attainment, gender, marital status, and household structure."

Across-state mobility has historically played an important role in our country's ability to recover from recessions. In a study published by the Brookings Institution, researchers carefully analyzed data from the four decades following World War II and found that mobility of workers across states was fundamental to the economy's ability to recover from negative shocks and to maintain low unemployment: "A state typically returns to normal after an adverse shock not because employment picks up, but because workers leave the state."

Mobility has fallen significantly in America since then. Two decades ago, about 3% of Americans moved from one state to another in a given year. Today, the mobility rate is half that. The government can help increase mobility by funding relocation subsidies for the long-term unemployed living in bad local labor markets. (For further discussion of such policies, see "Moving to Work" by Eli Lehrer and Lori Sanders.)

Relocation subsidies would help even those unemployed workers who choose not to move. If a significant number of unemployed workers leave a city, then the odds of landing a job go up for those who stay, because there are fewer job applicants for every vacancy.

There are downsides to relocation subsidies, of course. Conservatives stress the importance of community ties, which relocation subsidies would sever by design. In geographical areas hit hardest by a recession, this policy could cause long-term damage. What happens in the long run to a place like Detroit, for instance, if the government helps people to leave? These concerns could be mitigated, however, by offering the subsidies only to long-term unemployed workers in high-unemployment areas. The resulting departures would not be numerous enough to have a serious effect on community ties or the long-term economic health of an area.

PLAUSIBLE WAGES

A growing body of evidence finds that workers who are laid off suffer significant earnings losses even after they find a new job, and these losses can last for many years. For example, 15 to 20 years after being laid off from stable jobs during the early-1980s recession, displaced workers were earning 20% less than they would have had they not been laid off. One key reason is that a worker's skills will atrophy during an unemployment spell. Another is that changing jobs often means changing the occupation and industry in which you work, which in turn means a loss of productivity resulting from a steep learning curve. Many of today's unemployed workers are in this situation.

In a recent analysis, the National Employment Law Project tried to document which types of jobs were lost in the recession and gained in the recovery. Using data from the Current Population Survey, they classified 366 detailed occupations as either low-, mid-, and high-wage, with one-third of total employment in each category.

They found that all three occupation types lost jobs between the first quarter of 2008 and the first quarter of 2010 (roughly the period of the Great Recession) and gained jobs in the subsequent recovery. The pattern of job losses, however, was very different from the pattern of job gains. Mid-wage occupations accounted for 60% of job losses during the recession, but only 22% of job gains in the recovery. Low-wage occupations constituted 21% of recession job losses but 58% of recovery gains.

Not all workers who have lost their jobs can find new ones, of course, even if they are willing to switch to a new occupation or industry. In an important recent study, economists sent fake résumés to employers publishing real job postings in order to see whether unemployed workers were less likely to be granted a job interview solely because they were unemployed. The economists found that the probability of receiving a callback for an interview significantly decreased the longer the worker had been unemployed.

Why would a firm pass on a worker just because he happens to be unemployed? Firms can glean very little information about a worker from his résumé. Is the worker collegial? Conscientious? Reliable? Punctual? How long will it take the worker to ramp up and learn the job? In the face of all that uncertainty, and with many more job applicants than vacancies, firms can be scared off pretty easily from hiring long-term unemployed workers. In addition, firms may be less concerned about the fact that a worker was laid off than about the fact that no one else has yet hired that worker, inferring that other firms detected a problem during the interview stage.

For the more than 4 million long-term unemployed workers in the United States today, it is likely that some combination of all these factors is at play. Their lengthy unemployment spells are making it even harder for them to find work. Their skills are atrophying. They are trying to switch occupations and industries, but no one wants to give them a chance.

What can we do to help them? One promising reform might strike many as counterintuitive: Let firms pay them less.

A firm considering whether to hire a long-term unemployed worker has to form a judgment on how productive the worker will be. The firm will then want to match the wage it offers to the worker's expected productivity. But what if the firm thinks the worker will produce only, say, $4 per hour of goods and services? After all, the worker has been out of work for over half a year and has lost valuable skills. And the worker may be trying to switch industries or occupations, and likely will not be very productive in his new role for at least a few months. If the firm thinks the worker will be able to produce only $4 an hour, will the firm pay the worker the federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour? Of course not.

What if the firm is genuinely uncertain? The worker looks good — the firm thinks that after a few months he could be pretty productive — but the firm considers the worker a big risk. If the firm could pay the worker $4 per hour on, say, a four-month trial basis, then it would be more likely to hire him. But the federal minimum wage prohibits this. So the worker remains unemployed.

We should make sure that this doesn't happen by significantly lowering the minimum wage for the long-term unemployed for at least the first six months after the date they begin work at their new job. As with relocation subsidies, we should also lower the minimum wage for workers who exited the labor force after a period of long-term unemployment during the Great Recession. We should keep these policies in place at least until the employment rate for prime-age workers and long-term unemployment's share of total unemployment return to something resembling normalcy.

This would enable firms to take a chance on the long-term unemployed: Even if their contributions to the production of goods and services were small at first, the firm wouldn't lose money by employing them. This would give the long-term unemployed the opportunity to begin a résumé in their new occupation or industry, to learn occupation-specific and firm-specific skills that would increase their productivity in the future, to build a professional network in their new career, and to get their first foot back on the employment ladder. A lower minimum wage would help bring the long-term unemployed back into the ranks of the employed and hopefully would enable the first step to a second, better job — and a new career.

This proposal is not as radical as it sounds. We already exempt some workers from the federal minimum wage. The best known exemption is for workers who receive tips, like waiters at restaurants. Provided that an employee regularly receives more than $30 per month in tips, the employee can be paid as little as $2.13 per hour in direct wages.

There are several other notable exceptions. Some full-time students employed in retail stores or by colleges and universities can be paid 85% of the minimum wage, provided that they work fewer than 20 hours per week when school is in session and not more than eight hours on any given day. Workers under the age of 20 can be paid $4.25 per hour during the first 90 consecutive calendar days after the first day they are employed. The disabled can be paid less than the minimum wage, provided that the disability impairs the productive capacity of the worker. If these groups of workers can be exempted from minimum-wage requirements, then why can't the long-term unemployed?

To ensure that long-term unemployed workers are able to maintain an adequate standard of living in their new jobs, sub-minimum wages should be coupled with an expanded Earned Income Tax Credit or with wage subsidies exclusively available to the long-term unemployed.

These measures very well could end up being cost-reducing if they reduce the number of people receiving welfare benefits and if they keep people working and paying taxes when they otherwise would end up out of the labor force and possibly on the federal disability rolls. In any event, if we lower minimum wages for the long-term unemployed, subsidizing their wages would be a necessary complement.

The wage subsidies would have an additional important effect. Some long-term unemployed would rather remain unemployed and continue searching or exit the labor force altogether than take a low-paying job. By increasing the total rewards from working, wage subsidies will induce some unemployed workers to take a job they would not otherwise take. Indeed, conservatives should consider temporary wage subsidies for the long-term unemployed even if they are not coupled with sub-minimum wages. This marginal inducement will likely be more effective for the sizeable share of the long-term unemployed who never attended college and who are younger, but it may also prove to be enough of an incentive for some other long-term unemployed workers as well, particularly those trying to enter a new occupation or industry.

In addition to sub-minimum wages for the long-term unemployed, we should permanently lower the minimum wage for young workers. The same logic that applies to long-term unemployed workers also applies to the young: Firms will be more willing to take a chance on a worker who will be, for a while, relatively less productive if they can pay the worker a lower wage. A lower minimum wage would help young workers get started in the labor market, allowing them to find their first jobs. Skills would be developed. A professional network would be started. Soft skills like professionalism, punctuality, and collegiality would be cultivated. This would then lead to a second, better-paying job — and then hopefully a career.

Conservatives should recognize that society, including government, has a moral responsibility to do what we can to help the most vulnerable among us — a category that includes the long-term unemployed, especially in today's economy. Lowering the minimum wage would not completely solve the problem of long-term unemployment, but it would help. And to those long-term unemployed workers who ended up with a job because of a lower minimum wage, it would make all the difference in the world.

BEYOND ALL OR NOTHING

Imagine a firm with 100 employees. Each employee earns the same salary. A recession hits, and the CEO of the firm needs to cut payroll by 20% in order to stay in business. How does he proceed?

If he is a CEO in the United States, then he will likely lay off 20 workers. Those workers will be eligible for a weekly check through the unemployment-insurance system, which will cost the taxpayer about $300 for the average worker. In this example, taxpayers are on the hook for $6,000 a week.

Now, imagine that the CEO takes a different path. Instead of laying off 20 workers, he orders all 100 of his workers to stay home on Fridays, without pay. His payroll expenses are cut by the same amount as before — his firm can stay in business. Each worker can claim 20% of his unemployment benefit, so taxpayers contribute $6,000, just as before. But no one is laid off.

This second scenario is called worksharing. It involves two components: the redistribution of labor hours among workers with the goal of reducing involuntary unemployment, and short-time unemployment compensation to make up part of workers' lost wages through the unemployment-insurance system. Short-time unemployment compensation works in the same way as traditional unemployment compensation except that it applies to a reduction in work hours and not a layoff. Think of it as a prorated unemployment benefit.

At first blush worksharing looks like a flawless alternative to layoffs: The firm cuts payroll by the same amount of money, the expense to the taxpayer is the same, and no one loses his job. But there are some downsides. The workers who would not have been laid off are now taking in less income per week; instead of working full time, they are working 80% of the week and receiving an amount equal to only a portion (typically less than half) of what they would have made on Fridays in the form of a short-time unemployment benefit. If some of these workers leave the firm to find full-time work elsewhere, then the firm loses some of its best employees (the ones who would not have been laid off). It is reasonable to be concerned that, by discouraging layoffs during economic downturns, worksharing may discourage hiring during economic expansions; if it is harder to let workers go, then firms may be more reluctant to hire for fear that they won't be able to get rid of workers who turn out to be unproductive. Furthermore, if you believe that recessions are good in the long run because they re-allocate workers to more productive uses, then you will likely view worksharing as having a negative effect because it slows down this process.

Since worksharing would be voluntary for a firm, however, its negative effects on hiring and re-allocation would be significantly curtailed. Some firms genuinely need to restructure their workforces during recessions, and they should be able to do so without undue government interference.

A strong argument in favor of permitting worksharing is that it can guard against inefficient separations. Consider a firm with only a handful of workers that has exactly the workforce it needs at a given moment. A recession hits, and demand for the firm's products and services plummets. The firm can't afford to keep all its workers on staff, so it has to lay off one or two workers. If the layoff is temporary, then the workers sit at home losing valuable skills and may leave the firm permanently if they can find other jobs while they are laid off. If the layoff is permanent, then the firm loses the workers it most wants to keep — the workers whom everyone else at the firm is used to working with, and who have a great deal of firm-specific knowledge that often takes many months to acquire.

Worksharing would allow the firm to avoid this. It could weather a temporary lull in demand without having to substantially re-organize its labor force. The firm doesn't have to lose the workforce it has, and it doesn't have to incur the significant costs of replacing laid-off workers and training a new workforce once demand returns to normal.

In addition, worksharing may more equitably distribute the costs of recessions across the labor force. In our example of the 100-worker firm, under worksharing every worker would lose 20% of his salary, and some fraction of that would be replaced by a short-time unemployment benefit. The pain of the recession would be spread evenly across the workers. Without worksharing, the 20 workers who were laid off would bear all of the pain, while the 80 who remained would bear none.

A firm facing a demand shock should be left to choose whether worksharing or traditional layoffs offer the best course of action. But about half the states do not have a worksharing program in place, so firms in these states have no choice but to use traditional layoffs. (The firms could still shorten work weeks, but their workers would not be able to receive any short-time unemployment compensation. Firms understandably avoid this strategy.)

The Middle Class Tax Relief and Job Creation Act of 2012 included federal incentives to the states to set up worksharing programs. Many of the incentives in the act expire in the next year or two, and given the dismal state of the labor market it would be wise to extend them. And we should take steps beyond the incentives included in the 2012 law. All states should set up worksharing programs so that all American firms can have the option of avoiding traditional layoffs if they so choose.

In many cases, worksharing is better for firms and for workers than traditional layoffs. But firms can't use worksharing if they don't know it exists or if it seems too exotic and unusual. (Indeed, worksharing is hardly ever used, even in the states where it currently exists.) Beyond permitting the practice, public officials can also use the bully pulpit to let the labor market know about and get comfortable with worksharing. A vigorous public-relations campaign advertising and promoting worksharing is essential to influencing the behavior of firms.

Conservatives should support worksharing as a voluntary policy to help firms keep the workers they want, even in the face of a temporary drop in demand, and to help workers keep their jobs.

BACK TO WORK

Conservatism properly understood is deeply concerned about society's vulnerable and about the health and functioning of society more broadly. Consequently, conservatives should be concerned about one of the most immediate and serious economic and social problem facing the country today — our deeply troubled labor market — and about the millions of unemployed workers who are suffering, unable to find work to provide for themselves and their families.

Our unemployment crisis is certainly an economic crisis. We are losing a lot of income by having so many productive resources sitting on the sidelines, and (as some Republicans are always quick to point out) we are also spending a lot of taxpayer money on the social safety net.

But work is about much more than production, economic growth, and dollars and cents. Work harnesses our passions by channeling them to productive ends. Work gives us a sense of identity, a sense of purpose, and allows us to provide for those we love. Our unemployment crisis is therefore also a moral and spiritual crisis — a human crisis.

The solution to this crisis does not consist of massive short-term stimulus programs, industrial policy, cumbersome new bureaucracy, unnecessary regulation, and cronyist giveaways. Neither will the best solution be found in lower marginal income-tax rates, cuts in federal discretionary spending, and a balanced budget, whatever the benefits of such policies may be.

Instead, creative, genuinely conservative policies should be proposed and employed — policies that empower individuals, support their aspirations, increase their independence, help them to earn their own success, and promote virtue through work and personal responsibility.

Government should not sit idly by and watch the employment crisis. Indeed, government at every level has a central role to play in the effort to get the unemployed working again, and conservative policy solutions offer the prospect of success. It is time for conservatives to recognize this, and get to work.