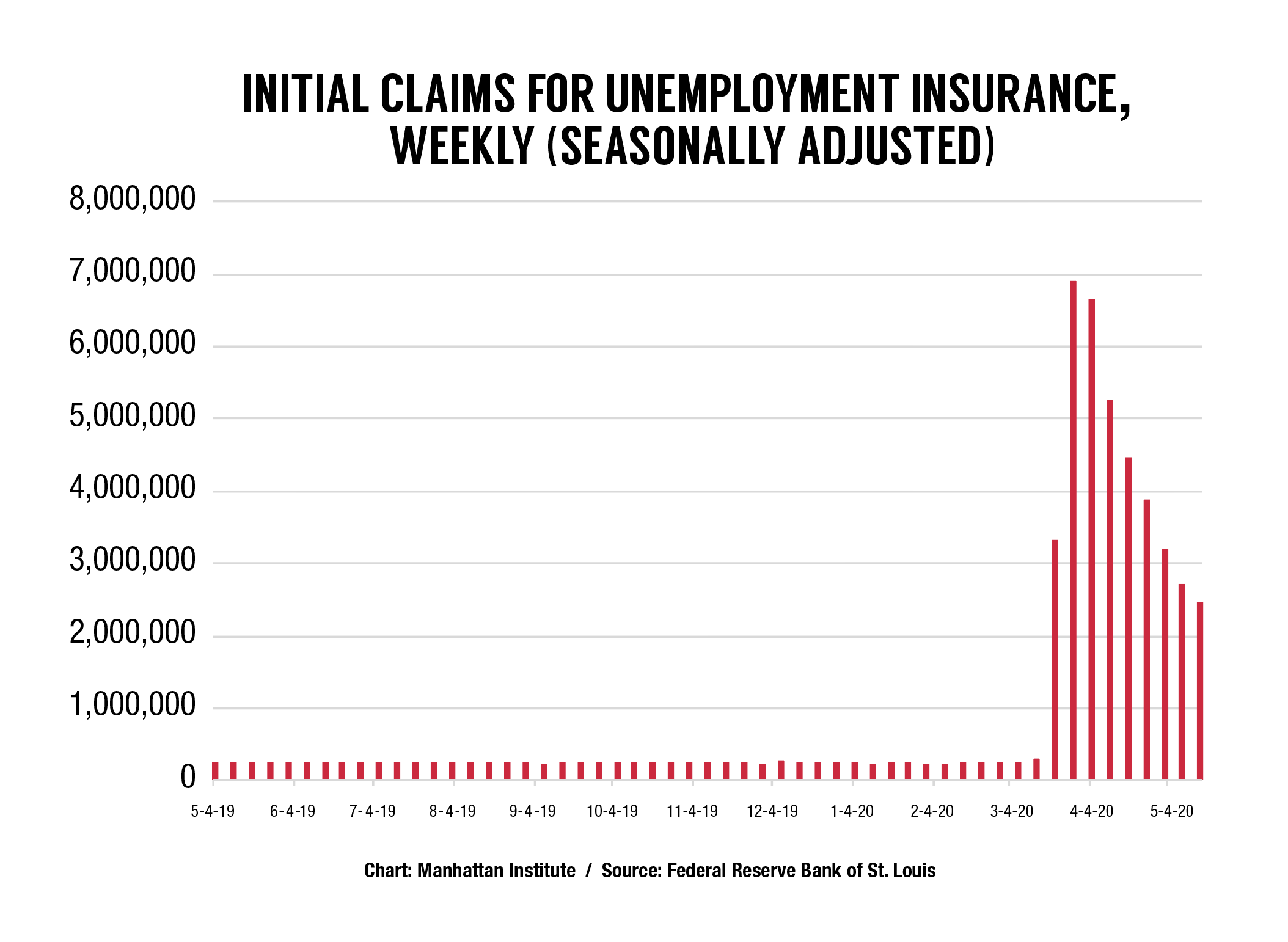

Over the past several weeks, since Covid-19 outbreaks have largely closed down the US economy, 36 million people have lost their jobs and filed for unemployment insurance benefits. For as many as two-thirds of them, a funny thing happened—they got a raise.

During normal circumstances, workers laid off from their jobs can get somewhere between 35 and 55 percent of their lost wages replaced by unemployment insurance benefits. Unemployment insurance programs are administered by states rather than the federal government, so the exact benefit depends on where the worker lives and the specific policies adopted in their state. This decentralized administration of unemployment insurance presented a challenge for lawmakers in mid-March as they sought to quickly pass legislation in the wake of the Covid-19 outbreak that would more completely replace the wages of the soon-to-be unemployed. The idea was to keep household budgets for laid off workers intact while the economy was put on ice.

Rather than create fifty unique programs to interact uniquely with the unemployment insurance program in each state, the CARES Act offered a simple solution: provide an extra $600 per week to each worker receiving benefits. This is the average amount needed to bring the weekly benefit paid to laid-off workers in line with what they were previously earning. But since this average includes some needing more than $600 to be whole and some needing less, the design of the Act mean that some were left with a hole in their household budgets while others ended up receiving more in benefits than they would have earned from working.

In one sense, this isn’t a terrible outcome. In the middle of an economic downturn, padding the budgets of laid-off, typically low-wage workers is an appropriate measure to offset other losses. In normal times, it might even work as an effective economic stimulus, since this group is likely to go out and spent those dollars, prompting even more economic activity. But since the slowdown isn’t being driven by a reduction in demand but rather an artificial halting of activity by regulation, that kind of stimulus won’t work.

And unfortunately, there is a downside to this sliver of abundance. As businesses across the country begin to reopen, albeit under significant restrictions, many will struggle to rehire workers who will both be earning more and protecting themselves from infection by staying home. Undoubtedly some, even many, may prefer working despite a small loss relative to unemployment benefits, but the perversion of incentives created by this policy may prove problematic for supporting a rapid economic recovery. Such a significant reduction in the incentive to work will almost certainly slow the rate at which laid off workers return to employment. The extent of the problem really depends on how quickly the pandemic is resolved. If conditions require restrictions on the capacity of businesses to persist, the disincentive to work probably won’t significantly constrain economic growth. If no jobs are to be had, we can worry much less about a program design that encourages people not to look very hard for work, and if there are future outbreaks it may even be desirable that people stay at home. But if reopening businesses aren’t forced to interrupt operations again because of further outbreaks, the way in which the Act is designed will hamper the economic recovery.

Regardless, the solution is for lawmakers to allow this relief benefit to expire as scheduled in July and replace it as needed with a program that replaces a high percentage of laid-off workers’ lost earnings without making it more lucrative to stay at home than to work. This could be accomplished by passing legislation that delivers block grants to states with conditions that funds be used in a prescribed manner. That way, states can decide how best to spend the dollars based on the current needs of their local economies, while not being allowed to use the funds to make up for their budget shortfalls. One way that a new program could help the unemployed is for the grants to be designed to match state spending rather than supplement it. This will prevent states from defunding unemployment programs when they receive the new stream of federal funding.

The current program for supplementing unemployment insurance benefits isn’t the best solution possible, but that’s understandable given the haste with which it was passed. Lawmakers now have a chance to get it right the second time around before we all pay too big a price.

Beth Akers is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and a former Council of Economic Advisors economist. Follow her on Twitter here.

Interested in real economic insights? Want to stay ahead of the competition? Each weekday morning, e21 delivers a short email that includes e21 exclusive commentaries and the latest market news and updates from Washington. Sign up for the e21 Morning eBrief.

Photo by Lisa Maree Williams/Getty Images