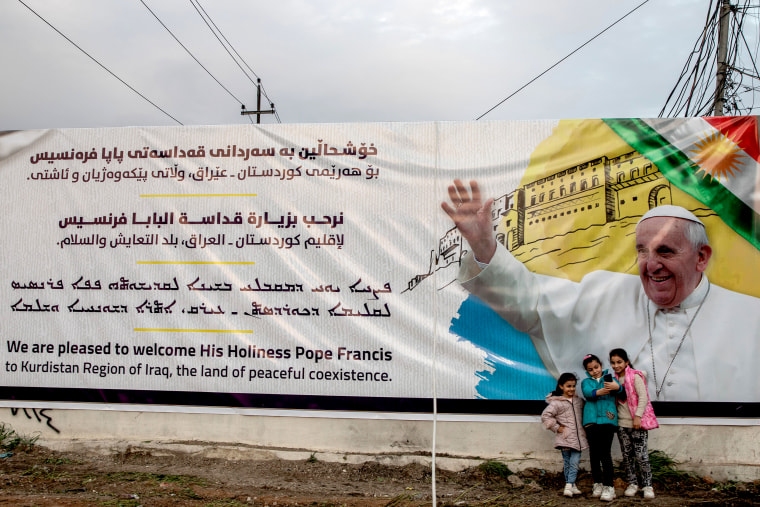

BAGHDAD — Pope Francis begins his first overseas trip since the coronavirus outbreak Friday. Of all the places he could travel to, he chose Iraq.

The pilgrimage to historic Babylon has been a dream of former popes — a visit to the birthplace of Abraham, patriarch of Jews, Christians and Muslims. But it also marks what is believed to be the first meeting in history between the head of the Catholic Church and the head of the Shia Islamic establishment — the Hawza — now led by Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, one of the most influential religious authorities in the Muslim world.

Though they come from very different backgrounds, I’ve been fortunate to see firsthand how strikingly aligned their personalities are.

The meeting between the 84-year-old pope and the 90-year-old ayatollah is a profound statement about the importance of tolerance and dialogue in a turbulent region where too many people believe violence is a solution to fix broken societies. Both Francis and Sistani have consistently condemned violence committed in the name of religion.

That the meeting is a private affair in the modest home of the ayatollah in Najaf, without the pomp, protocol and entourage normally associated with a visiting head of state, makes the similarities between these two men even more pronounced. I've been fortunate to see firsthand how strikingly aligned their personalities are, even though they come from very different backgrounds.

As the grandson of Sistani's teacher and predecessor and as an Iraqi participant in a Vatican conference on ending violence in the name of religion, I have been honored to meet both religious leaders. I have seen that they both convey calm and humility despite their influence, just as they both embrace a philosophy of tolerance and compassion for the most vulnerable in society.

Although the meeting is a brief one, I believe its impact will be felt across the Middle East. The Shia Islamic world is divided between a mainstream, Iraq-based school of Islam that believes there should be a separation of church and state and a revolutionary, Iran-based school that believes in theocracy. The meeting with the pope represents international and interreligious recognition of the mainstream Iraq-based Shia school.

This recognition provides an important morale boost for the people and organizations in Iraq and the greater Muslim world who have been working on interfaith dialogue for years but who are often dismayed that international awareness of Shia Islam so often revolves around the violent militant groups. This will hopefully lead to a strengthening of their efforts.

The Hawza is not an institutional equivalent to the Catholic Church, but Sistani is the closest Shia Islam has to a pope, leading a seminary established in Najaf in the 11th century. The Hawza is like a university and a church rolled into one, with colleges spread throughout Iraq and the region that train clerics in traditional Islamic studies, such as jurisprudence, Quranic exegesis and theology, and it also provides spiritual leadership for the world's about 250 million Shia Muslims.

Unlike other state-sponsored Islamic institutions around the world, the Hawza of Najaf prides itself on financial, political and intellectual independence from any government. It relies on grassroots funding from Shia Muslims around the world. In what is thought to be a first, the pope will be meeting an Islamic authority in the Middle East who is neither a government official nor sponsored by a government.

Iranian state media have been conspicuously quiet about the papal visit. But the significance hasn't gone unnoticed. Mehdi Nasiri, a journalist and former representative of Iran's supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, raised eyebrows when he tweeted an acknowledgment that the meeting between indicates that the "traditional" school in Iraq has overtaken the "modern" school in Iran in understanding global priorities and religious diplomacy.

In Iraq itself, the contrast between these two schools is clear. While Sistani calls for strengthening the Iraqi state and its institutions and emphasizes the need to create a civil state, there remain powerful Iran-backed militant groups that actively undermine the state, ruthlessly cracking down on dissent and running parallel security forces.

Since the pope's meeting with Sistani has focused local and international media attention on the peaceful, tolerant voices in the region, some of those militant groups are uneasy about it. Fake news is even being spread on social media that Sistani has Covid-19. The militants might not care much about international public opinion, but they do notice that the overwhelming majority of Iraqis — including the main Shia Islamist political parties and religious groups — are welcoming the visit. They like to portray themselves as defenders of the faith and of the country, but on this issue they are clearly out of step.

Iraqi history, of course, has never been a fairy tale for its ethnic and religious communities, but there are encouraging signs despite the destruction and violence that have seen the Christian population in Iraq shrink from 1.5 million in 2003 to less than half a million today. In 2014, when the Islamic State militant group declared Mosul its capital, only 17 Christians were studying at the University of Mosul. Now, there are 863. ISIS was determined to destroy Iraq's pluralism and diversity, but Iraqis are even more determined to preserve them.

Some say the pope’s visit is a message of peace from the world to Iraq, while others say it is a message of peace from Iraq to the world. The reality is that it's both.

Francis' visit to churches in Baghdad targeted by Islamist terrorists and his visit to Mosul in the north — where Christians and other religious minorities, such as Yazidis and Shias, faced genocide — also send a reassuring message to these indigenous communities about their importance to the social fabric of Iraq and their relevance to the broader world.

Iraqis from all backgrounds have been looking forward to the pope's visit, which is a recognition of not just Iraq's rich history, religious significance and demographic diversity, but also of the pivotal role the country can and should play in building bridges between communities across the region and around the world.

Some say the pope's visit is a message of peace from the world to Iraq, while others say it is a message of peace from Iraq to the world. The reality is that it's both.